Sewing Knits – A primer from Threads Magazine

We have been using our downtime to update our class schedule. We’re getting pretty excited about some new classes that we’ll be offering in the new year!

One class will be Knits Lab and we cannot wait to share with you all our tips and tricks for sewing knits and jersey fabrics. It’s really not that hard. We swear!

In our searching for class ideas we came across this great tutorial from Threads Magazine on sewing knits and thought we must share it with you.

By Ann Person

From Threads #73, pp. 42-45

Let me quickly dispel the apparent mystery about sewing with knits: there isn’t any! Nonetheless, after 30 years of writing and teaching on the subject, I’m always surprised to find out that these supple fabrics still alarm many sewers. And nowadays there are so many new knit fabrics available, it’s hard to know how to handle them all. So I’d like to present a basic primer of information every sewer needs to create knit garments that look like ready-to-wear. And believe me, it’s easy— you don’t have to be an expert.

The great fun of sewing with knits is the leeway they give you when fitting. A garment made from a stretchy fabric doesn’t have to fit as perfectly as one made from a woven, so knits eliminate the pressure of exact measuring and altering of patterns. And they’re so comfortable to wear!

When constructing knit garments, the first rule is that if the fabric stretches, the seams must stretch, too, so that the stitching won’t pop as you bend and move in the garment. Whatever type of machine you have, I’ll show you how you can achieve flat, stretchy seams.

Check out the fabrics!

Whether made of cotton, wool, linen, one of the new synthetics, or a blend, each knit falls into one of several construction categories: single knits (created on a commercial knitting machine with a single bed of needles); double knits (created on a double-bed machine with two back-to-back beds of needles); and rib knits (made by alternating stitches between two needle beds). Single-knit fabrics like jersey, velour, terry, and fleece look different on the reverse side, have cut edges that curl, and usually have about 25-percent stretch. Double knits like interlock (made with fine yarns) tend to be more stable than single knits, often look the same on both sides, have cut edges that don’t curl, and stretch from 25 to 75 percent, depending on the fiber and construction. Rib knits, constructed from alternating knit and purl stitches in various combinations, may look the same or different on opposite sides, tend not to curl, and have up to 100-percent stretch.My philosophy for fabric preparation is to always pretreat a fabric before you sew it exactly as you plan to care for the finished garment. This means that cotton, linen, and synthetic knits should be washed and dried (in the dryer if you plan to dry them this way later), and wool knits should be thoroughly steamed before cutting.Smart pattern choices

When planning a knit garment, I recommend selecting a pattern specifically designed for knits, rather than for woven fabrics, because the pattern will have the correct amount of ease built into it. The amount of stretch in the fabric will determine the style and size pattern you choose. Check the pattern envelope for suggested fabrics and the amount of stretch required for the style. If you choose a fabric with less stretch, you’ll need to add more ease.Since knit fabric has built-in ease, you don’t need as much ease in the pattern as you would for a woven fabric. A couple of inches of bust ease, for example, is plenty for a fairly fitted knit style, compared with the 5 in. of bust ease needed for many woven garments. And a double-knit skirt hangs nicely with 2 in. of ease, while a woven skirt would require at least 3 to 4 in.

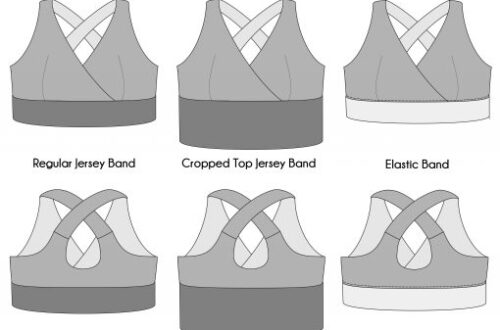

Construction optionsYou can get successful results on knits whether you own a basic sewing machine or the latest high-tech serger. I began sewing on knits long before I owned a serger, and I still recommend my original technique of sewing with a long straight stitch of 9 sts/in. (3 mm), stretching the seam as I sew it (as much as the fabric stretches easily) to add elasticity. When the seam returns to its normal length, the stitches are closer together and the upper and lower thread tensions have loosened. As for using zigzag or stretch stitches to construct seams, I’ve simply never liked them.

For double knits that will stay pressed open, use a 5/8-in.-wide seam allowance. For single knits that tend to curl, I recommend a 1/4-in.-wide seam, which you can finish two ways: either press it to one side and topstitch for a professional look, or sew a second line of stitching 1/8 in. from the first and then press to one side. The double-sewn seam adds strength and helps keep the seam flat.

If you have a serger, you’ll find serging a quick way to assemble knits with a finished, factory look, and the seams will have built-in elasticity, so you don’t need to stretch them as you sew. Make sure your stitch is balanced, adjusting the thread tension so that the stitch doesn’t bind or ruffle the seam. If your serger has differential feed, raise the setting if your test seam looks wavy. For hemming soft knits, I find that serging the edge, turning up a 1/4-in. hem, and topstitching twice gives a stable, nonslippery finish.